She was sold to a man when she was 15 years old, had a baby and eventually was rescued. She was Guadalupe Martinez Rios, my grandmother.

After her ordeal, she had four more children with my grandfather and worked in a factory and as a servant for a French family in Mexico City. She died from leukemia. The life of my mother, like her mother before her, was harsh. For breakfast, it was café negro (black coffee) and, if she was lucky, a piece of bread. My mother escaped poverty thanks to her love for education – she became a teacher and years later, one of the few trauma-orthopedic female surgeons in Mexico City. Known as la doctora Rios, my mom’s education did not protect her from the chronic stress of working in a dominant male environment, where women were devalued. She died from septic shock in a hospital in Mexico City a week after my son was born. Amidst the sorrow of losing her, my son brought hope and strength back into my life so that in 2018, I defended my dissertation on the mental health of labor trafficking survivors.

This essay is also available in Spanish

Shortly after my defense, I read investigations conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor against 35 agricultural employers in five Michigan counties for violating migrant housing and child labor laws. The Department of Labor found that children under the age of 12, including one 6-year-old, were picking blueberries in the fields. Their stories resonated with me perhaps in part because they shared elements of my mom’s and grandmother’s harsh – and sometimes exploitative – working conditions.

As seen in my grandmother and mother, people’s gender, ethnic, racial and economic positions intertwine with precarious employment and exploitative working conditions. Precarious jobs often feed from the social vulnerability of the workers, potentially leading to exploitative working conditions – with labor trafficking as the most extreme form. This dangerous mix is harmful to people’s health, demotes human rights and impacts all of us.

If you add climate change’s effects on agricultural production – for example, extreme temperature and precipitation can destroy crops – you’ll find agricultural workers already working in precarious conditions even more vulnerable: not only they are exposed to even hotter temperatures, but they are pressured to work faster to account for production losses. As expressed by a female farmworker that I interviewed in southwest Michigan, “there are many hours of bending [when working picking cucumbers]. Many of us have pain in the waist and legs. Sometimes the heat is intolerant. [I got] headaches when the heat is strong and we are there, working hard.”

However, as a society we can change this by demanding enforcement of fair and safe working conditions for farmworkers. Integrating the enforcement of worker’s rights and protections with climate change in mind will further social and environmental justice for all.

The harsh reality of farmworkers in Michigan

Maria Luisa Rios, author's mother.

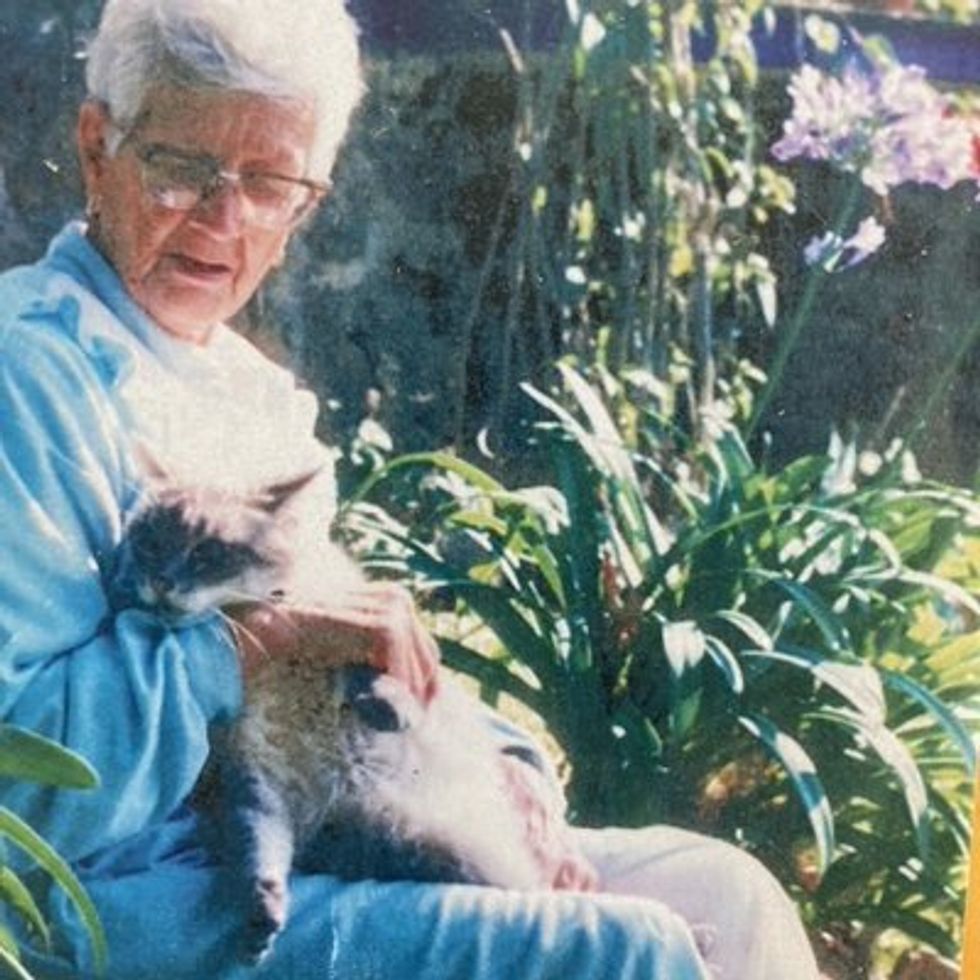

Guadalupe Martinez, author's grandmother.

In 2018, I attended a conference on human trafficking and met an attorney with roots in Honduras with years of experience providing legal services for farmworkers in Michigan. After meeting her, I connected with organizations and advocates working with farmworkers in the state. These conversations and my trips to agricultural working sites to meet workers lead to the development of the Michigan Farmworker project, which started after I got a position as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Michigan. The first study started in 2019. The goal was a more in-depth understanding of the working and living conditions of farmworkers in Michigan. I interviewed farmworkers and individuals in education, health care, community leadership, social work and law providing services to farmworkers.

Related: Nayamin Martinez on organizing for farmworker justice

The interviews highlighted the harmful effects of precarious work and exploitative labor practices. A male farmworker conveyed: “When you are not useful to them [referring to growers], they threw you away like a banana peel. He [the grower] wants his production, that you do the work, and if you are not one of the people that follows what they want, they fire you.” Similarly, a female farmworker expressed, “I felt like we were animals. All day being bent down and (working) quickly, quickly and without breaks and drinking water.”

Wage theft is common, someone working in legal services told us: “There are varying degrees of exploitation. And the most common one we see is just wage theft when growers don’t pay the minimum wage for hour, they’re just stealing someone’s labor. And then charging them for rent [when they should not], [and other] unauthorized deductions of their paychecks.”

Social vulnerability, fear and gender inequality were captured in the quotes of these two female farmworkers: “Because many [farmworkers] don’t bring papers [referring to being undocumented], that’s why they don’t talk [referring to presenting complaints]. They are afraid that they’ll get fired, and then, what are they going to do?”

“We have to follow the rules, because otherwise, where are we going to go? We don’t have anywhere to go and, worse, nowadays there are a lot of H-2A workers. They [growers] want single people, single men, that don’t have families.”

Michigan farmworkers harvesting apples.

Credit: Michigan Farmworker Project

Michigan farmworkers loading up a harvest.

Credit: Michigan Farmworker Project

Why is this happening to farmworkers?

The situation of farmworkers is not unique: about four of five American workers in insecure or part-time minimum wage jobs are projected to experience poverty at some point in their lives. Latino full-time workers are 4.5 times more likely than white full-time workers to earn below the federal poverty line and nearly one in three Latino full-time workers fall below 200% of poverty.

The erosion of human and labor rights particularly affects farmworkers in the U.S., as farmworkers have been excluded from labor protections like minimum wage, workers’ compensation, overtime pay provisions or the right to unionize.

These inequalities are product of decades of free-market policies that limit taxes and regulations, privatize public services like healthcare and retirement, obstruct or eliminate labor union rights, erode working conditions and safety standards, promote low-wage work and, in general, move away from social protections and emphasize personal responsibility for the choices (including health) people make. These social and economic conditions are a breeding ground for precarious and exploitative work.

Climate change and extreme heat

Climate change is exacerbated by these same economic systems and policies.

Economic systems that value wealth at the expense of the exploitation of individuals and natural resources exacerbate climate change. However, those same systems are extremely reliant on the natural conditions that climate change is eroding. Currently, 34% of jobs in G20 countries – the world’s major economies – are in farming, fishing and forestry, and these jobs rely on natural processes and resources like pollination, soil renewal and fertilization and moderation of extreme temperatures – all threatened by climate change and environmental degradation.

The disruption caused by climate change negatively impacts the economic activities and jobs that depend on the environment and natural resources, which leads to further exploitation of workers and those same resources. It’s a vicious cycle.

Related: How workers’ rights and environmental justice movements collide in California’s Central Valley

A clear example: Extreme heat events threaten agricultural and food systems – as they can cause crops to fail – but they also accentuate health inequities in the farmworker population, as they create hazardous working conditions. As a male farmworker relating the death of a worker in the field told me, “a friend of my friend died. He came to work in Georgia in the watermelon crop. He was telling to other worker that came to help him that he was feeling sick and the other workers laughed at him and dismissed him. He went then to sit under a tree and he got a heart attack and died. He died because the sun was too strong.”

Heat related death events are not uncommon among farmworkers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2008 that U.S. crop workers are 20 times more likely to die from heat related illness than U.S. civilian workers overall. While this is the most current data, it is plausible that this threat is the same if not worse given that temperatures continue to rise.

The way we treat people and the environment has to change

Apple harvesting in Michigan.

Credit: Michigan Farmworker Project

Addressing precarious employment and labor exploitation has to go hand in hand with addressing climate change. The way we treat people has repercussions in the way we treat our environment, and vice versa. Recognizing the essential role of farmworkers in the U.S. requires the modernizing of the country’s Fair Labor Standards Act provisions to enforce labor policies and regulations, raising the minimum hiring age for farmworker children, support farmworker’s rights to unionize, increase wages and enforce minimum wage payments instead of relying on payment per unit of fruit or vegetable picked. Providing social protections benefits such as health insurance, pension, overtime compensation, paid sick leave and training opportunities for workers and families are ways to enforce labor rights while protecting them from the effects of climate change.

The imminent threats of global climate change on labor, including heat related illness in farmworkers, demand investments in climate-related infrastructure like public health surveillance systems, which can be helpful to assess the effectiveness of different preventative measures and needs in this vulnerable workforce. To ensure a sustainable future for farming that protects the health and safety of its workforce, we need all members of the agricultural community, from agribusiness executives to employers of farmworkers, to support policies that integrate environmental and labor-related objectives.

Finally, an essential step to decent working conditions means acknowledging the vital role of farmworkers in the U.S. by giving them the opportunity to earn legal status. As one male farmworker told me: “To improve the [working] conditions, the only thing I see it’s to provide papers [legal documentation] so we do no need to endure mistreatment.”

I am a third generation survivor of human trafficking. My grandmother survived, but many perished. As individuals and society, we cannot normalize or ignore that labor exploitation exists for those working in our fields and ignore the stories that farmworkers in Michigan shared during their interviews.

Human flourishing occurs in a society that supports public health, a healthy workforce and a healthy environment. Farmworkers are a strong and resilient community that make important contributions to the economic and social fabric of this country. Improvement and enforcement of labor standards can mitigate climate change, and gives us the opportunity to become a better society that protects human rights and environmental health for all.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

- Mobilizing against pesticides from the ground up ›

- Adrift: Communities on the front lines of pesticide exposure fight for change ›

- New country, same oppression: It’s time to bolster farmworkers’ rights ›

- How workers’ rights and environmental justice movements collide in California’s Central Valley ›

- As masses of plaintiffs pursue Roundup cancer compensation, migrant farmworkers are left out ›

- LISTEN: Lisbeth Iglesias-Ríos on advocating for migrant farmworkers’ rights - EHN ›

- LISTEN: How becoming a mother changed these researchers - EHN ›

- LISTEN: “Dehumanizing” conditions for Michigan farmworkers - EHN ›