DURHAM, NC—On a school night in early spring, a rowdy collection of environmental activists, local residents, and Duke University faculty and students packed a public forum, railing against the school's plan to build a new $55-million gas plant on campus.

For nearly three hours, speaker after speaker denounced fossil fuels, decried fracking, and inveighed against the state's investor-owned utility. They begged the university to invest in a "sustainable future," one filled with wind and solar power, not natural gas.

But Tim Profeta, the chair of Duke's sustainability committee and the host of the meeting, had another idea. "We have an opportunity to become a demander of biogas, and not the fracked gas we've been hearing about all night," he said.

Since 2007, Profeta said, the university had been researching the capture of methane from hog manure to create electricity. The technology, called anaerobic digestion, could reduce pollution from the state's 10 billion gallons of swine waste – now stored primarily in open-air pits – and help meet a campus-wide goal of zero net greenhouse gas emissions.

Many in the crowd that night were skeptical. Was it really feasible?

A select group of faculty, staff and students thought it was. Two weeks after the forum, the panel made its recommendation to their university's top brass: only build the new plant if, within five years, Duke could purchase enough swine biogas to fuel it.

Campus leaders – who had been working toward a vote to approve the plant during a May board of trustees meeting – temporarily shelved their proposal.

The subcommittee's proposition was, in some ways, an elegant one. Long concerned about the pollution created by the state's 9.2 million hogs, the university helped pioneer a first-of-its-kind swine-waste-to-energy project in Yadkin County, North Carolina, in 2011.

By committing to make a major purchase of swine biogas, Duke believes it could spur the creation of nearly 300 similar-sized projects – more than doubling the number of anaerobic digesters on livestock farms nationwide, and creating useful lessons for a fledgling U.S. biogas industry.

The influx of projects would curb emissions of methane – the potent greenhouse gas many times more powerful than carbon dioxide – and cut odor and pathogens emanating from some of the state's 2,100 large-scale hog operations. It would create hundreds of short-term construction jobs and some long-term ones in rural areas of the state that sorely need them.

But critics see a messy side. They worry the benefits of methane capture are too limited, and could preclude more comprehensive cleanup of an industry that has anguished some neighbors and polluted waterways for decades. And though many climate analysts believe biogas can play a small but important role in displacing fossil fuels and reducing greenhouse gases, they say that doesn't justify the university's investment in expensive new gas infrastructure.

"Biogas is a perfectly laudable goal, and as a leading university in the country in a state that produces this much pork, it would be a very fine thing to incentivize and get going," says John Steelman of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who also happens to be a Duke graduate. "But don't link that to building a new gas plant."

For the moment, the university staff is trying to figure out how to make the swine gas recommendation a reality. Their success or failure could reverberate throughout the nation's biogas market and across other North Carolina campuses with commitments to reduce their climate footprint.

Biogas: A two-pronged attack on climate change

By curbing both carbon dioxide and methane, biogas plays a dual role in the steep greenhouse gas reductions that scientists believe are necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change.

To ratchet down carbon dioxide pollution, analysts say society must use less energy overall, and transition the entire economy to rely on clean electricity rather than burning coal, oil and natural gas.

Most researchers agree wind, solar and other non-combustion sources could get the country to almost 100 percent clean energy. But with today's technology, "nobody knows how we're going to get the last 5 or 10 percent," says Rob Sargent with Environment America.

That's because processes that require extremely high heat – like the production of plastics needed for medical devices – still rely on combustion. Jet planes and long-haul trucks still demand a liquid fuel source to travel great distances.

Thus, though he's generally circumspect on biogas, Sargent acknowledges, "there are some applications where it makes sense in the transition to straight-up renewables and storage."

Others say biogas could prove vital over the long term in decarbonizing society's hard-to-electrify elements – from heavy-duty vehicles to the gas stoves consumers may be loath to give up.

"The value of biogas … is really is an alternative for direct gas use for non- buildings, non-electric generation areas," says Amanda Levin of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who recently authored a strategy for cutting U.S. greenhouse gases 80 percent by 2050.

Most analysts believe biogas will play a small part in displacing fossil fuels. Levin's study, for example, found it would make up just 4 percent of all gas use by mid-century.

But biogas would play a vital role in curbing methane. Believed to be 36 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas, methane is far more prevalent in the atmosphere than previously thought, according to groundbreaking research published last year.

In 2015, the most recent year analyzed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, methane accounted for 10 percent of the country's greenhouse gas emissions. Natural gas drilling is a significant source of methane, but the agency's data show agriculture – through a combination of cattle digestion and livestock manure – is still the single largest source of the pollutant.

Thus, even if biogas plays a minute role in reducing carbon dioxide pollution, most researchers say there's ample benefit in displacing methane leaks from natural gas, and averting methane pollution wherever possible. Case in point: if the Durham plant could spur the creation of 289 more digesters the size of the Yadkin County one, the methane captured would cut as much greenhouse gas pollution as removing more than 175,000 cars from the road.

"Capturing the energy is better than not capturing the energy," Sargent says.

An investment that risks increasing fossil gas dependence

Despite the value of biogas in curbing global warming pollution, many advocates believe new infrastructure shouldn't be built to burn it – especially if used to create heat and electricity, two purposes that could be served by non-combustion renewable sources.

Fueling existing combined heat and power plants with biogas rather than natural gas – as the University of California system is considering – makes sense, they say. But a new power plant that would divert resources away from other clean energy investments does not.

"Duke is culturally resistant to making the kind of investments that will fundamentally change their energy system to something that is either all-electric, or gets away from steam as a general heating tool," Steelman says. "You're baking this added capacity into your long-term resource plan in lieu of more aggressive investments in efficiency and renewables."

Finally, there's concern that the plant could be built on a promise of biogas that never materializes – a particular worry since the proposal reflects a nationwide push by utilities to build combined heat and power plants on college campuses.

The ‘devil’s in the details’

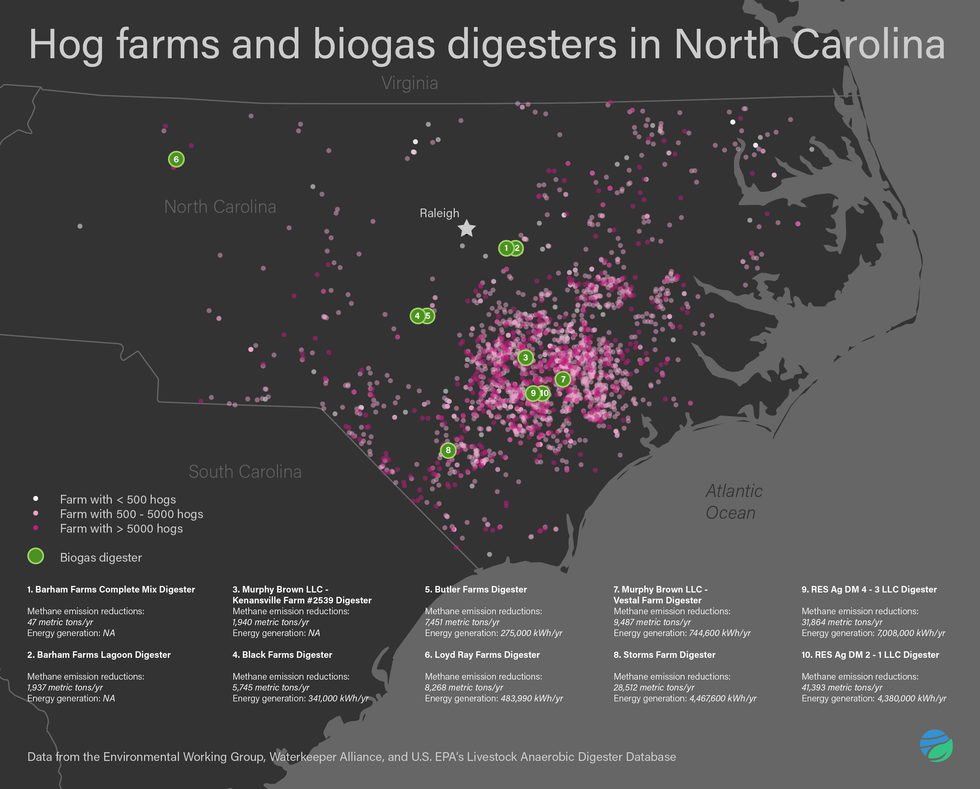

Graphic: Kaye LaFond

Undoubtedly, the U.S. biogas market needs a kickstart. According to the American Biogas Council, of all the wastewater treatment plants, landfills, and livestock operations around the country that could economically capture methane, only about 14 percent do so at the moment.

By sheer number of facilities, the agricultural sector represents the country's greatest room for growth – with 8,700 swine and hog farms large enough to economically produce biogas, but just 265 on-farm digesters operating today.

Dairy farms make up the bulk of these, most in the Midwest, where farmers have sought to allay neighbor complaints about the smell of manure spread on fields. Dry cow manure is easily collected from already-confined animals and funneled to an above-ground tank, and its energy output is high.

Hog waste, however, has a high liquid content and produces less gas than dry cow manure. It's typically stored in open-air pits and costlier to move to a separate tank. And though the anaerobic digestion process can take place in a covered pit, or "lagoon," it relies on warm temperatures.

Those factors help explain why Iowa, which raises more hogs than any other state, has only two swine-waste-to-energy projects – and why Minnesota, which ranks third behind North Carolina in hog production, has none. And they point to how North Carolina – with its warm climate and hefty hog population – has become a pioneer in swine biogas, with 10 digesters now in operation and more soon to come online.

Still, with the third most biogas resources in the country, North Carolina lags far behind its potential – and its progress toward swine gas has come in fits and starts.

Some of the reasons are unique to the state: hurricanes and the spread of disease wiped out hog populations, reducing waste and the fuel they could produce. Also, out-of-state developers with expertise in energy but not hogs signed deals that fell through.

"They look at a map and they see all the swine farms and they see dollar signs," says Angie Maier with the North Carolina Pork Council. "But as with anything, the devil's in the details. It's very difficult to pull one of these projects off."

But other hurdles are common for biogas projects across the U.S. Like all emerging renewable energy sources, swine gas is more expensive than traditional fuels – which enjoy direct subsidies and no obligation to pay for the impacts of their pollution. In North Carolina, Duke Energy estimates biogas is roughly three times the cost of natural gas.

"Biogas systems are no different from any other renewable energy system in that they have to be conceived in a way that makes money," said Patrick Serfass, head of the American Biogas Council. "That's a challenge right now for the industry."

Policies designed to help level the economic playing field for biogas have been erratic over the last decade.

After Republicans swept the North Carolina legislature in 2010, they launched regular campaigns to repeal the state's 2007 clean energy mandate – which included a small but crucial swine-waste-to-energy requirement. A bipartisan majority always thwarted these attempts, but the signal to would-be biogas entrepreneurs was chilling.

"The industry needs the regulatory environment to be consistent," says Brian Barlia of Revolution Energy Solutions (RES), the project manager for one of the state's largest biogas projects to date, in Duplin County.

Removing a pillar that allowed an RES development in Magnolia, North Carolina, to turn a profit, in 2015 lawmakers also ended the state's 35 percent tax credit for renewable energy investment – one of the most generous in the nation.

Similarly, the U.S. Congress let a 30 percent investment tax credit for biogas projects expire in 2016. After that, Barlia says, "your two main economic drivers have been put to pasture." Without them, he says the Magnolia project – which came online in 2013 – would not have penciled out.

Selling electricity to regulated utilities also poses challenges. Though a 1978 federal law requires utilities to purchase power from small renewable energy developers, negotiating contracts and connections to the electric grid is no easy task for most farmers.

"We don't have a lawyer on staff," says Deborah Ballance, who, with her husband, runs Legacy Farms in North Carolina's Wayne County, where a digester system will be up and running in six months. "We had to go out and find someone who was knowledgeable about this. It's not every day you deal with a power company."

Ballance is one of the few who overcame other obstacles facing farmers considering building and running a digester themselves: lack of capital to invest in a system that can run $1 million or more, and the knowledge or inclination to apply for government grants that could assist them.

Even hosting an outside energy developer like RES is a significant decision for a farmer. "No matter how good the deal may look," says Gus Simmons, the state's leading biogas engineer, "there's no way that doing any of these projects doesn't change the farmer's world."

‘Heads begin to nod’ on biogas

But biogas proponents in North Carolina see signs of hope. Some of the Legislature's most rabid clean energy opponents have retired, while others are softening their views.

Duplin County's Rep. Jimmy Dixon, a "semi-retired" hog and turkey farmer, has co-sponsored bills to repeal or freeze the renewable energy law every legislative session since he joined the North Carolina House in 2010.

Now he says, "repeal is a bygone proposition at this point. We've invested too much time, energy, and human capital. People have complied with the law and they shouldn't have the rug pulled out from under them."

A sweeping, bipartisan clean energy law adopted this summer also may indicate a new era of magnanimity toward renewable fuels – and it includes a section prodding the utility to perform "expedited review" of swine waste-to-energy projects seeking interconnection.

Quicker reviews and connections, says Duke Energy's Travis Payne, "that's going to be a priority going forward."

Growing numbers of companies and campuses are joining Duke University in pledging 100 percent clean energy and "carbon neutrality," sustaining a voluntary market in which biogas producers can sell credits for curbing methane emissions. Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork-producer, has even committed to reducing its climate footprint by 25 percent.

According to the Pork Council, interested growers are meeting regularly with energy developers, the utilities, and university researchers to understand their options. Among farmers, there's more interest than ever before.

"Five, six years ago, if I was talking to groups of farmers [about biogas], I didn't have their full attention," Maier says. "Now, I see their heads nodding."

‘Most people looking at renewable natural gas’

With approximately 24,000 feet of underground pipes, the RES biogas plant in Duplin County pumps gas from ten digesters to different domes like this one, which fuels a generator that produces electricity and waste heat. (Credit: Elizabeth Ouzts)

One of the greatest sources of optimism for biogas proponents is the trend toward "renewable natural gas": removing impurities from methane and injecting molecules directly into existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure, as opposed to generating electricity onsite.

Sometimes called "directed biogas," the approach is already being used with swine waste-to-energy projects in Indiana, Missouri and Oklahoma. It means farmers or biogas developers don't have to negotiate with the electric utility to connect to the grid. What's more, burning renewable natural gas in a high-efficiency power plant produces more energy than less efficient on-farm generators could.

That's part of why Duke Energy plans major renewable natural gas purchases from two projects within the next year. Both in Duplin County, one will become the largest anaerobic digester in the nation – drawing on poultry and food waste as well as hog manure. The other, designed by the same engineer who helmed the Yadkin County project for Duke University and Google, comes online this month.

"We're trying a lot of technologies to meet our swine goals," says Duke Energy's Payne. "But honestly we're putting a lot of eggs in the directed biogas bucket."

There is some debate over what standards biogas must meet before it can be injected into pipelines and renewable natural gas still carries some added costs – cleaning the gas isn't cheap, nor is the infrastructure needed to connect farms to existing pipelines. In 2013, however, a Duke University study found pipeline injection of biogas could lower the cost of swine biogas to as little as 5 cents a kilowatt hour.

Renewable natural gas also opens the door for additional incentives – particularly critical in the wake of expired tax incentives for swine waste to energy. If the biogas is ultimately converted to transportation fuel, it can qualify for credits under the nation's Renewable Fuel Standard.

"That credit has a value, and it's a game changer. You can sell your [unit of gas] for $43 as opposed to three [dollars]," says Serfass of the American Biogas Council. Thus, "most people are looking at renewable natural gas these days just because of the enormous revenue upside."

Yet Duke University believes biogas will never really take off in the state – or perhaps the country – without an additional catalyst: Such as a wealthy school willing to pay top dollar for nearly as much biogas as state law already requires.

Tanja Vujic, who works in the office of the executive vice president at Duke University, and helped get the Yadkin County project off the ground, emphasizes their procurement would be on top of the existing swine gas requirement.

"There's not been a demand signal like this before, and there's not been such a motivated buyer before," she says. "Those two things together could really accelerate things."‘The top of our list’

A one-time staff member of the Environmental Defense Fund, Vujic believes the university can play a vital role in not just jumpstarting the state's market for waste-to-energy, but in paving the way for new manure management practices that take less toll on the surrounding waterways and communities. But, she says, "it's not all going to happen in one fell swoop."

As of this publishing, the university has made no new proposals public on the plant, or its plans to procure biogas. But Vujic is confident the campus will make it happen. "That's what my job is," she says. (Indeed, in the months since the power plant controversy first blew up, her title has changed to "Director of Biogas Strategy.")

Vujic's goals go beyond the subcommittee's recommendation. Her aim is to procure enough biogas not just to fuel the new power plant, but to displace all of the university's existing natural gas use – an outcome that, if done in connection with ramping down energy use overall – might appease some of the plant's sharpest critics.

Vujic is also hopeful the university's procurement can create models that can be exported throughout rural America, as the agricultural industry stakes out its role in mitigating climate change.

But most of all, she says Duke University is trying to minimize its climate footprint and maximize its benefit to North Carolinians. When she and her colleagues survey all the options, "methane from hog farms always comes out at the top of our list."

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms. This story was done in partnership with NC Policy Watch.