YADKIN COUNTY, NC—A blanket of gray hangs over the hills, refracting the late July sun and sealing in a thick scent of gas and compost.

Gus Simmons is sporting gray Levi's, a navy golf shirt, and a salt and pepper buzz cut.

The engineer climbs on top of what looks like a giant, charcoal-colored sail laid flat on the ground, anchored with a crisscrossing network of pipes, and billowing nearly head-high. Like a kid in a bouncy castle, he bounds across the rubber, covering half the distance of a football field.

Beneath him are 2.1 million gallons of animal feces. Behind him is a row of nine oblong barns, their fans blowing the stench from the thousands of hogs packed inside. Behind to his left, a contraption the size of a large cupboard creates electricity.

Simmons is conducting a tour of Loyd Ray Farms – a nearly 9,000-head operation in the northwest corner of the state.

Called an anaerobic digester, the rubber-covered-pit-of-excrement is Simmons' proud creation. Microscopic beings in the oxygen-deprived crater seize on the hog manure, separating it into methane gas – burned to create power for more than half the farm – and liquids, which are piped to an adjacent pond.

Simmons dashes to the pond. He flips a switch, creating powerful rapids. This reintroduction of oxygen, called aeration, reduces ammonia and other pollutants in the liquids before they are sent to an earthen pit for storage and irrigation.

Raised on a farm that he says grew "a little bit of everything," from hogs to row crops, Simmons has made his life's pursuit the design and construction of biogas systems like this one – the first of its kind in the state. But his work has implications far beyond Yadkin County.

Because anaerobic digestion reduces pathogens, odor, and volume, it offers a critical upside for managers of all types of organic byproducts – from animal manure to food waste to sewage. Harnessing methane gas – which would otherwise leak into the atmosphere – curbs a global warming pollutant many times more potent than carbon dioxide. And converting the gas to energy displaces fossil fuels, creating a small but crucial sliver in the renewable energy pie scientists say is necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

But challenges remain. Renewable gas is more costly than traditional fuels. Transporting it from the rural areas where it is produced to the urban areas where it's often needed can be difficult. And many would-be producers of biogas – from wastewater treatment plant operators to hog farmers – still lack the expertise, the will, or the capital to adopt the technology.

If Simmons and his colleagues can overcome these hurdles in North Carolina, they can set an example for policy makers, renewable gas developers, and others nationwide.

"Let me chat about odor for a second. Those of you who've been on hog farms before, I hope you notice that it's different," he says to the tour group, of the smell coming from the hog houses. Simmons implores them to note the more pleasant scent of the aeration basin. "I'm an eastern North Carolina farm boy. We used to plow bottomland, and you would smell this organic, earthy smell," he says, wistfully.

"That's what it smells like to me."A reflection of the local area

The science of anaerobic digestion described by Simmons is one that has evolved over hundreds of years.

In the 17th century, a Belgian scientist discovered that decaying organic matter created a substance, "far more subtle or fine…than a vapour, mist, or distilled oiliness, although…many times thicker than air." From "chaos," Jan Baptista van Helmont coined the term "gas."

Nearly 200 years later, British scientists determined this gas was methane. In 1859, the first biogas plant was built at a leper asylum in India. By the end of the 19th century, small digesters were popping up in India and along the coast of southern China.

Today, the size and manner of digesters varies widely across the globe.

"One of the universal truths of biogas systems is that they reflect the local area," says Patrick Serfass, head of the American Biogas Council.

Simple household digesters are widespread in rural parts of the developing world, where there's no electricity, natural gas, or centralized sewage treatment. Some 40 million people use them in China.

Europe, by contrast, leads the world in commercial-scale biogas, with more than 17,000 systems. While the circumstance in each European nation varies somewhat, says Serfass, "if there are two common denominators, it's high electricity prices and no space for landfilling."

He quickly adds, "those are two we don't have here, which is why the U.S. market is so different."

America has long had a vast network of pipelines and transmission lines, cheap electricity, and ample room for dumps. As a result, biogas development has lagged. Just more than 2,000 systems are now in operation, according to the American Biogas Council, the majority at sewage treatment plants to reduce volume.

And although the council estimates at least 8,700 dairy and hog operations in the country are large enough to profitably produce biogas, only 265 – 12 percent of them swine – do so.

But the tide may be turning. New sources of renewable energy are needed to replace gas, coal and oil, and stave off climate change. Analysts now recognize methane emissions from farms as a significant source of global warming pollution. And there's growing concern about food waste, which is now the single largest component in the nation's landfills.

‘So many hogs, so much manure’

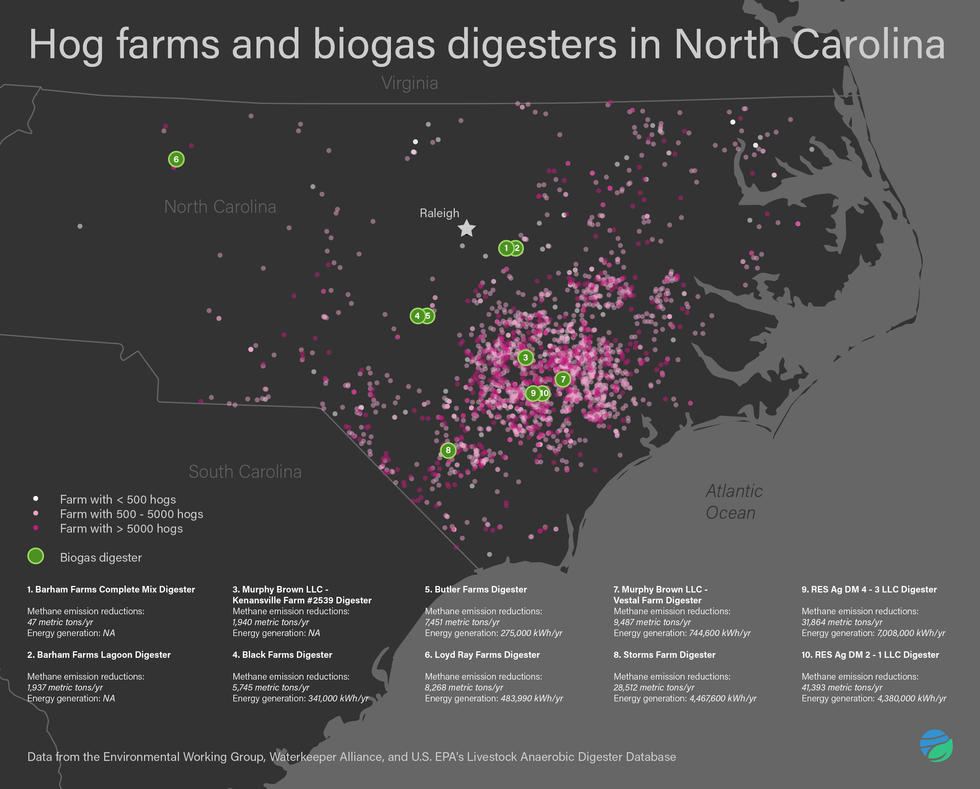

All of these elements are at work in North Carolina, home to 10 of the nation's 32 swine-only biogas systems, more than any other state. But in evidence of Serfass's "universal truth," the main factor driving renewable gas here is a local phenomenon.

"There are just so many hogs, and there's so much manure, and it has to be managed," he says.

Concentrated in the southeastern part of the state, North Carolina's 9 million hogs – the second most in the country after Iowa – are largely the property of a handful of corporations. In a system pioneered by Duplin County's own Wendell Murphy, these corporate integrators contract with growers, many of them former tobacco farmers, to raise the animals. The integrators supply the growers with feed and ship the pigs to slaughter.

The contract farmers are left to manage the pigs' waste – 10 times that produced by a human. Most follow the same template: A clutch of rectangular sheds with slatted floors house hundreds of animals. Manure drops beneath the slats to a pit beneath the sheds, from which it is flushed into one or more open, earthen pits. Periodically, the liquid from these pits is sprayed onto nearby fields to irrigate and fertilize low-value crops like hay, which can stand the onslaught of nutrients.

It's a strategy that may have worked well in 1980, before the state's hog population skyrocketed and thousands of hogs were concentrated on fewer and fewer farms, encroaching on streams and homes. But today, critics say, such handling of 10 billion gallons of swine manure each year poses grave problems for the environment and public health.

Heavy rains and hurricanes can cause open waste pits to burst and overflow. At least 14 were flooded last fall when Hurricane Matthew dumped 15 inches of rain in the eastern part of the state.

Nutrients from spray fields are also appearing in nearby rivers and streams, producing algae blooms and in extreme cases, fish kills. One study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found swine operations causing water quality violations in 60 percent of nearby waterways.

At the same time, odors and pathogens from hog houses and sprayed liquids are tormenting and even sickening neighbors, according to the more than 500 eastern North Carolina residents who've filed a nuisance lawsuit against Murphy-Brown, LLC, the company Wendell Murphy built and sold to Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork producer.

Public awareness of these issues peaked in the 90's, forcing state leaders to attention. Before then, says Christine Lawson of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, "there were no regulations."

Among the most significant new rules of the decade, state lawmakers enacted a moratorium on new hog operations with more than 250 animals – unless they met tight standards for odor, pathogens, nitrogen, ammonia, and discharges into waterways. As part of an agreement with the Attorney General, Smithfield and Premium Standard Farms funded research into "economically feasible" measures, including methane capture, that might allow farmers to meet the new limits.

After more than a decade of wrangling, in 2007 the legislature passed two major laws that determined the industry's trajectory for another decade.

First, as part of a sweeping renewable energy measure, lawmakers created the nation's only requirement for electricity produced from swine gas. "I don't think anybody knew whether it would work or not," says longtime former legislator Joe Hackney, a Democrat who was then serving his first term as Speaker of the House. "It was well worth a try."

In a second law, the Legislature made permanent the ban on new or expanding industrial farms that didn't meet strict environmental standards, created a fund to help incentivize biogas production and other pollution control measures on existing farms that promised not to expand, and launched a pilot program on methane capture.

"It was a balance of the interests of the parties so that a bill could be passed," Hackney says. "The industry was trying to save itself."

The deal was bittersweet for activists who'd been fighting industrial-scale waste pits, or "lagoons," for years. "We were able to come up with a ban that says there will be no new lagoons in North Carolina," says Larry Baldwin, the longtime Lower Neuse Riverkeeper who now works with the national network Waterkeeper Alliance. "But the ones that are here are still here, and they're still creating havoc environmentally and in the communities."

Moving the ball along

Loyd Ray Farms' aeration basin and anaerobic digester. (Credit: Elizabeth Ouzts)

Financed by Duke University and Duke Energy, and later by Google, Inc., the $1.2 million-dollar system at Loyd Ray was the first project to take advantage of both 2007 laws.

The utility counts the 600-megawatt hours of electricity generated – enough to power the biogas system and five of Loyd Ray's nine barns – toward its requirements under the renewable energy law. The university takes partial credit for the methane captured, the equivalent of removing 900 cars from the road, to offset some of its on-campus pollution and achieve its aim of zero net greenhouse gas emissions. Google claims the rest of the methane reductions to meet its own goal of 100 percent renewable energy.

A condition of receiving state incentives, the Loyd Ray system also goes beyond methane capture to meet the standards for odor and nutrient pollution, established in the moratorium law. The state funding also prevents the farm from expanding, but its owner and namesake, Loyd Bryant, has no plans to do. Instead, he's happy for the electricity generated, and the chance to do some good.

So is the surrounding community, says Tanja Vujic, who leads Duke University's efforts to research and procure biogas, and helped steer the Yadkin County project. "We had a ribbon cutting for the system after it was up and running. I had people come up to me who were neighbors." Unsolicited, Vujic says, they told her that they had been unhappy living near the farm – but now they could no longer smell it.

But some members of the July tour group weren't that impressed.

Elsie Herring, who lives next door to a hog operation in Duplin County, is one of the hundreds suing Murphy-Brown. She kept her nose covered for the bulk of the trip.

Lana Carter, who lives a mile and a half from a swine operation in Bladen County, also reacted to the stench. She was unconvinced the irrigation water was as clean as billed. "At the end of the day, they're still spraying it," she says.

Another concern: why was the waste-to-energy project so far west, on the only swine farm in the predominantly white county? Why weren't the mostly black communities in southeastern North Carolina getting any relief?

"It's going to be a while before they get to my neighborhood," says Carter, who is African American.

The other nine digester systems operating in the state are all to the east: one in Bladen County, one in Johnston, two in Harnett, the rest in Duplin. But none are meeting the strict environmental performance standards that Loyd Ray does – even with state incentive funds or the promise of expansion, no one could make the investment pencil out.

That's why Vujic and other backers of the Yadkin County project hope it can be fine-tuned, made more cost-effective, and implemented widely in the heart of hog country.

"Loyd Ray was just: 'we know we can do this, and we have to meet these standards, and this is our chance to move the ball along,'" Vujic says.

But some question the value of exporting the Loyd Ray model. Baldwin, of the Waterkeeper Alliance, believes biogas capture alone – without additional environmental safeguards – simply props up the old lagoon-and-sprayfield system. Plus, he worries the benchmarks met in Yadkin County may be too lenient.

"Even the Loyd Ray farm, it's better than what we have, but to me it's not enough," he says.

The standards may sound good, "but if they're not strong enough, what have we accomplished?" he adds.

In the coming months, Legacy Farms in Wayne County will put the standards to the ultimate test. Using a slightly different technology – in which dry bedding as well as hog manure is directed to a series of digesters and retaining ponds – the farm will become the second after Loyd Ray to meet additional limits on odor, nutrient, and pathogen pollution. They will exempt the farm of over 560 acres from the moratorium, allowing it to expand from 5,500 sows to 60,000 "finishing" animals.

Deborah Ballance, who runs the farm with her husband, is one of the state's few farmers completely independent from Smithfield or another integrator. The expansion allowed by the new system will allow the Ballances to raise animals until they are ready for slaughter.

"It wasn't working for us having to sell the weaned pig," she says. "It was better for us to maintain control throughout the whole process. This was a way for us to do that, and to keep our family farm."

She didn't say exactly how much the new system would cost, but did acknowledge it was in the millions. "I'm probably never going to retire," she says, chuckling.

Ballance lives on her farm, right next to the hog houses, as does her grown daughter and her family. She says they try hard to be good neighbors and have had no complaints. And, she noted, "we're right here – the first ones that are going to smell anything."

Putting together pieces of the puzzle

Gus Simmons walks between the anaerobic digester and aeration basin he designed and installed at Loyd Ray Farms in Yadkin County, North Carolina. (Credit: Elizabeth Ouzts)

Despite the example of Legacy Farms, most observers don't believe there's demand for a dramatic increase in the total number of hogs raised in North Carolina, due to slaughtering capacity, available land for new and expanded farms, and other factors.

"I've not heard any serious conversation, anywhere, about expansion," says Andy Curliss, head of the North Carolina Pork Council. "Any type of biogas project, it's much more about dealing with what exists now."

"If there is any pent-up potential in North Carolina," says Kelly Zering, an agricultural economist at North Carolina State University, "it may be to relocate and concentrate existing pig production capacity."

The main appeal of biogas for the swine industry is the opportunity to turn a byproduct into an asset, Zering says in an email. Aside from that, "producers and integrators may find some non-monetary benefits, such as improved perception of them by neighbors and others in the state, as well as by investors and others outside North Carolina."

Some in the industry are already reaping these "non-monetary benefits" by hosting third-party renewable energy developers on their property.

Take Washington, D.C.-based Revolution Energy Systems (RES): The company operates two waste-to-energy systems in Duplin County in the tiny town of Magnolia, which has a population of about 1,200 people and is 40 percent Hispanic and almost one-third black.

Together the two new systems create 17 times as much electricity as the Loyd Ray project in Yadkin County.

The projects use the waste from more than 70,000 pigs, raised on ten adjacent operations under one owner, Murphy Family Ventures, a company started by Wendell Murphy's son.

Waste from the barns is scraped into a small holding tank that separates liquids and solids. Liquid is piped into a cylindrical, above-ground digester tank, two stories high and two rooms wide, painted a gleaming royal blue that lends an air of industrial efficiency.

Unlike Loyd Ray, there's no aeration pond for excess liquid; instead it's pumped directly into the lagoon that predated the digester. Even so, there's virtually no odor.

Gas is piped underground and stored in a white, futuristic-looking sphere. The contents are channeled to an electric generator; the waste heat is redirected back to the digesters to control the anaerobic process.

Like Loyd Bryant, Murphy Family Ventures incurred no cost for the biogas system, including retrofitting its barns with scrapers. Instead, the system is owned entirely by RES, and so are its benefits: renewable energy credits sold to Duke Energy to satisfy the 2007 law; methane credits equal to the pollution of nearly 7,500 cars sold on the offsets market; waste heat to aide digestion; revenue from electricity sold to the grid.

"From the host, to the utility, to the state, everything needs to be in harmony to make this happen," says Brian Barlia of RES.

‘Learning with every step’

A decade ago, when the swine biogas requirement became law, there was no sheet music for producing that harmony. Only a couple of swine farms around the country were capturing methane and creating electricity. There was no one right combination of scrapers, digesters, and onsite electricity generation, or guidelines for connecting to the electrical grid of a regulated utility.

"We were just scratching the surface of swine waste to energy," says Republican Rep. Jimmy Dixon, a "semi-retired" swine and turkey farmer from Duplin County, and one of the hog industry's staunchest defenders. "We were way, way, behind. We weren't on the starting line when the whistle was blown."

The result, says the Pork Council's Curliss, is that "everybody is trying everything."

Lawson, the engineer at the state's Department of Environmental Quality who has permitted all of the state's swine-waste-to-energy projects, has seen a range of schemes – from simple, covered lagoons, to multi-farm projects like RES's Magnolia. "There's experiential learning with every step," she says.

One Duplin County farm, called Vestal Farms, says Lawson, "has tried a menagerie of things," but none lasted. Now, that farm is part of a concept that's generating buzz in the biogas world.

Instead of burning gas onsite to create electricity – an added expense and operational burden – farmers can purify the molecules and inject them into the existing pipeline infrastructure. Customers can pay for a certain amount of "directed biogas" or "renewable natural gas" to be injected – in the same way some utilities allow customers to pay for a certain amount of renewable energy to be added to the electrical grid.

In November, an endeavor called Optima KV begins inputting biogas into a pipeline in Duplin County; Duke Energy will use it to help fuel its gas plants in Wayne and New Hanover counties.

It will become the largest biogas project in the state, large enough to power more than 800 homes, and the first to inject directly into a pipeline system. Five different farms, including Vestal, have invested in the system and will reap its benefits.

Unsurprisingly, it's the latest waste-to-energy innovation from Gus Simmons. And while Simmons is excited about the possibilities of renewable gas, he sees a future in which all the state's farms are, by one method or another, converting their waste into an asset.

"I think there's an opportunity for all of these farms to find a way," he says.

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms. This story was done in partnership with NC Policy Watch.

Related: Hog waste-to-gas: Renewable energy or more hot air?