"In 2014, my world changed forever when I learned my family was exposed to contaminated drinking water containing high levels of PFAS. Since then, I haven't stopped worrying about my family's health," says Andrea Amico, a New Hampshire resident and PFAS community advocate turned national activist.

"Impacted communities didn't get a choice in their exposure. We were contaminated without our knowledge or consent. And now we have to grapple with anxiety and worry that our immune systems could be harmed by PFAS contamination that could make us more vulnerable to COVID-19."

Andrea isn't alone. She's one of many leaders across the country who live in PFAS-exposed communities that fear for the lives of their families and how their PFAS exposure will affect their ability to fight COVID-19.

PFAS are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a class of chemicals used since the 1940s to make products non-stick, waterproof, and stain-resistant. They're used in rain jackets, carpets, upholstery, cookware, fast food packaging, dental floss, and much more.

Dubbed 'forever chemicals' due to extreme environmental persistence, they've been found in environmental samples worldwide. An estimated 110 million American residents have PFAS in their tap water, partly due to widespread use in certain firefighting foams; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found PFAS in the blood of most Americans.

PFAS also have been linked to many health effects including high cholesterol and cancers, even at low levels of exposure.

Most concerning during this global pandemic, however, is that exposure to PFAS suppresses the ability of the immune system to make antibodies—the part of the immune system critically important in fighting COVID-19 and other infectious agents.

Exposed children have been reported to have decreased responses to common childhood vaccines, an impairment that lingers into teenage years. Studies of adults exposed to PFAS also have shown diminished responses to flu vaccines.

Our studies have found that laboratory animals exposed to PFAS have decreased antibodies, verifying what we have seen in PFAS-exposed people and making us confident that PFAS are toxic to the immune system.

Just last month, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry issued a statement about the potential intersection between PFAS exposure and COVID-19 and cited findings linking PFAS exposure to reductions in antibody responses to vaccines and resistance to infectious diseases.

Unlike other synthetic chemicals that affect the immune system, such as polychlorinated biphenyls and trichloroethylene, PFAS are unregulated by the U.S. government; currently there are no federal drinking water standards for PFAS.

As well as being 'forever chemicals' in the environment, PFAS can remain in human bodies for days, weeks, months, or years. This means that as we take PFAS into our bodies each day, through the water we drink, the food we eat, and the products in our homes and workplaces, some remain behind and build up in our bodies over time.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a drinking water "health advisory level" of 70 parts per trillion for two individual PFAS, but this advisory isn't an enforceable standard, so public water supplies aren't required to monitor or treat water to remove PFAS. Furthermore, this guideline only addresses two of more than 5,000 individual PFAS and is not low enough to protect the sensitive immune system, especially in children.

The public needs to be protected from PFAS in their drinking water with a legally enforceable federal standard. We support the EPA's efforts in moving forward with such standards for PFAS.

Current policies that allow these chemicals to remain in the environment, drinking water, and commonly used products are putting human health, and our future, at risk. The chemical industry continues to add these chemicals to products despite knowing that they're toxic and the EPA still approves new PFAS formulations for the market.

But together we can create a better future.

The responsible thing to do is shift to healthier products through changes in policy and management, consumer demand and education, investment in safer alternatives, and community action. These shifts require bold, coordinated action, but if we work together, we can create a healthier and more resilient future.

Andrea Amico's family was exposed to high levels of PFAS through drinking water contaminated by firefighting foam at a former Air Force Base.

She stays awake at night worrying about long term effects PFAS will have on her family's health, but now has the added burden of worrying if they're more at risk of contracting COVID-19, of experiencing symptoms longer, and when a vaccine is available, if it will be effective enough to protect her family due to the potential impacts of PFAS exposure on their immune systems.

"This global pandemic is scary for everyone and it's even scarier knowing your family has been exposed to chemicals that may hurt the immune system when it's needed most."

Author's affiliations: Jamie DeWitt, East Carolina University; Phil Brown, Northeastern University; Courtney Carignan, Michigan State University; Shaina Kasper, Community Action Works; Laurel Schaider, Silent Spring Institute; Cheryl Osimo, Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition; Maia Fitzstevens, Silent Spring Institute.

Andrea Amico of Testing for Pease contributed as well.

Their views do not necessarily represent those of EHN, The Daily Climate or publisher, Environmental Health Sciences.

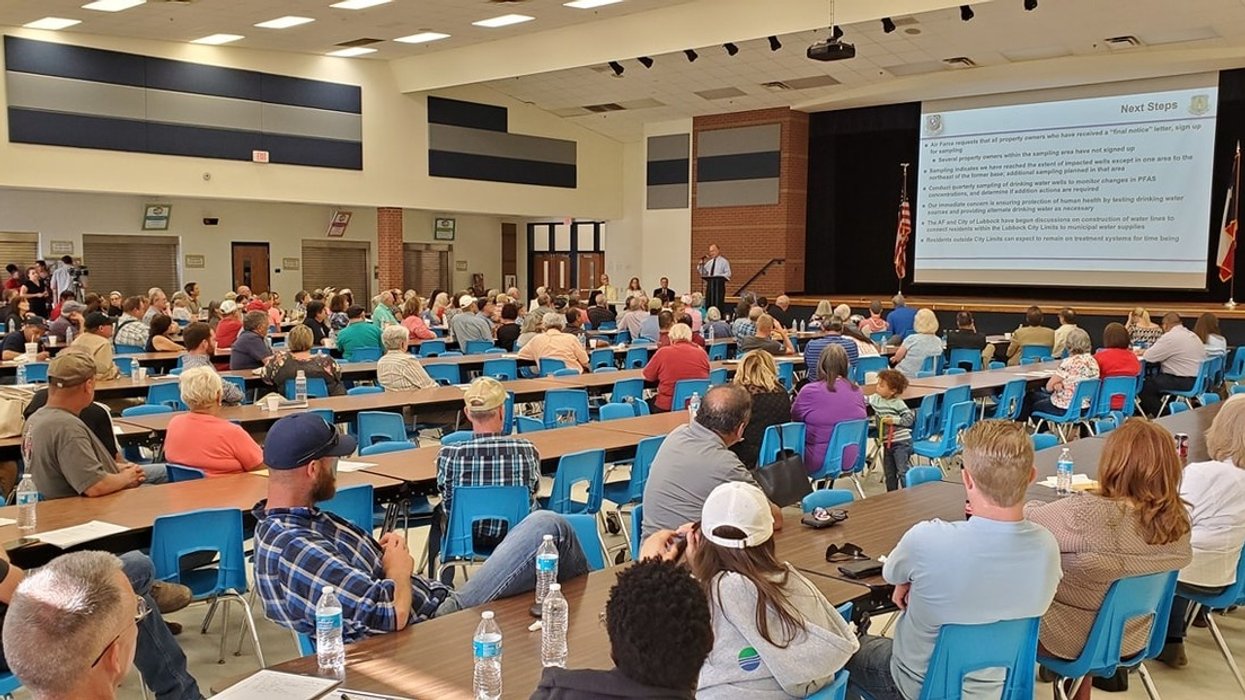

Banner photo: Air Force meeting on PFAS contamination. (Credit: AFCEC/Malcolm McClendon)

- Fake News blocking progress on PFAS Action Act: Op-ed ›

- The real story behind PFAS and Congress’ effort to clean up contamination: Op-ed - EHN ›

- 7 things the White House should do to limit PFAS pollution - EHN ›

- CoverGirl Sued For PFAS contamination - EHN ›

- PFAS widespread in water- and stain-resistant outdoor clothes, home linens - EHN ›

- Investigation: PFAS on our shelves and in our bodies - EHN ›

- What are PFAS? - EHN ›

- Unintentional PFAS in products: A “jungle” of contamination - EHN ›

- LISTEN: Theresa Guillette on what gators and crocodiles can tell us about our health - EHN ›

- PFAS in household waste may be going airborne - EHN ›

- How Colorado is preventing PFAS contamination from the oil and gas industry - EHN ›

- PFAS removal discovery not yet a ‘powerful solution’ - EHN ›

- Tests find PFAS abundant in some dental floss - EHN ›

- PFAS-polluted North Carolina alligators have weakened immune systems - EHN ›

- Evidence of PFAS in sanitary and incontinence pads - EHN ›

- Not only are PFAS toxic — they’re bad at their job when applied to furniture - EHN ›

- Are you putting PFAS on your eyeballs? - EHN ›

- Opinion: Why PFAS have no place in everyday products, including paint - EHN ›

- Back-to-school: Avoid PFAS in your kids’ backpack - EHN ›

- PFAS can enter and accumulate in the brain, study confirms - EHN ›

- What will the EPA’s new regulations for “forever chemicals” in drinking water mean for Pennsylvania? - EHN ›