CLEAR LAKE, Iowa—Chris Petersen has raised two children, thousands of hogs, a couple of rambunctious terriers and hell.

Lots of hell.

"The family farm is gone," he says tapping his kitchen table with gnarled workingman's hands, the fingernail on his index finger busted and purple. "And someone needs to know about it."

He shows me a local newspaper with an above-the-fold photo of him rallying a crowd against a proposed mega-hog farm. "Top story of the year," he says.

He speaks casually of driving presidential hopefuls around the state, offering reality. "We took John Kerry to a pile of dead hog stacked up on the side of the road, you know what he asked? 'Why are they all dying?' That's when he got it," Petersen says.

The "it"? A way of life that has industrialized over the past 30 years, undergoing a massive makeover. Hog raising has become faster, more efficient, more lucrative. Demand for pork is soaring worldwide: per capita consumption has shot up 7 pounds over the past 30 years.

To keep up, farmers raise hogs predominantly inside massive confinement barns and work for the handful of large corporations that dominate the market.

These changes have brought well-publicized pollution concerns. In Iowa, pig manure is so pervasive in waterways that the state has declared 750 of them impaired. And in North Carolina this year, researchers found pig poop bacteria on the homes of 14 out of 17 farm neighbors they tested.

But the most profound impact? Big Ag has upended rural communities, taking the fruits—meat and produce—from America's breadbasket and leaving a host of social, economic and environmental injustices behind: Plummeting home values, pressure that drives small farmers into tight contracts or out of business, shrinking populations and a diminished political voice in small rural towns.

For Petersen, preserving the rural farm life he loves now means regularly driving 40 miles in a night to attend a rally, butting heads with industry titans, visiting DC to buck the corporate farming trend. And dealing with the occasional death threat.

The 62-year farmer still raises a couple hundred black Berkshire hogs a year at his home off a dirt road here. He rocks back in his chair with Kirby, his terrier-greyhound mix, along his side. Petersen had the chair made four inches wider so Kirby could sit with him.

He shrugs off the death threats. "Somebody has to stand up," he says, tugging on his "America 1776" hat.

In every metric Iowa presents the poster child of hog farm consolidation and growth. Last year Iowa smashed a record—the state reached 22.4 million hogs, 7 percent higher than the year before and 30 percent higher than a decade ago, based on USDA data.

While the pork sales soar, an economic injustice plays out in Iowa communities.

Industry contraction means fewer farmers. That puts towns at an economic crossroads. The Iowa Economic Development Authority projects that due to consolidation, agriculture is the only major state industry that will lose jobs—approximately 1,850 over the next decade. Iowa, still overwhelmingly rural, had 6,321 new jobs in its 88 rural counties over the past five years, while the 11 metropolitan areas had 3 times that job growth, according to the Authority.

While small businesses in Iowa increased almost 30 percent over the past decade, the average number of non-farm small businesses per county declined about 25 percent in counties with large hog farms.

This runs counter to industry claims that consolidation and contract farming opens new markets and opportunities to farming communities.

"While ownership is much more concentrated, production is still spread out," says David Miller, director of research at the Iowa Farm Bureau. "Do you get rich doing it? No. But hog finishing is coming back as point of entry for people that want to farm for a living."

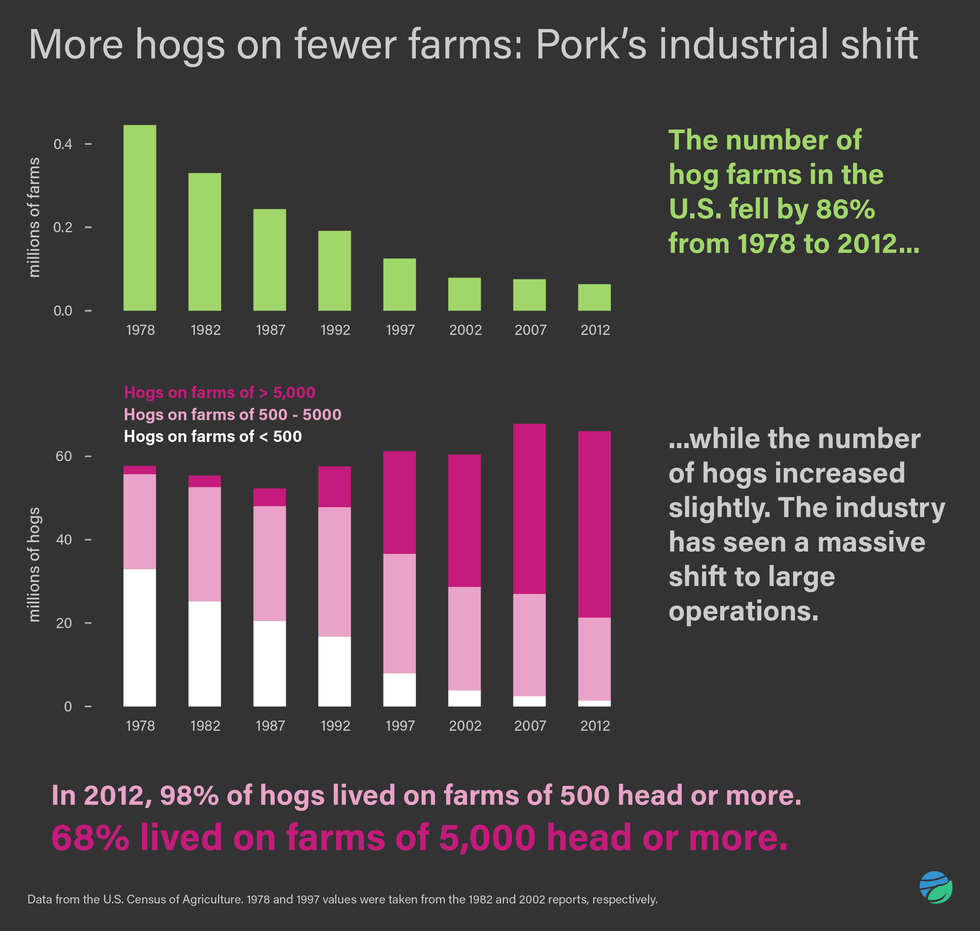

However, over the past four decades, the number of hog farms has plummeted by 90 percent. In 1977 the USDA counted more than a half million hog farm operations. Today the latest census reports 63,236. Our taste for cheap bacon and pork chops isn't the only force driving this contraction. As developing countries' economies grow, pork is one of the first indulgences of the newly empowered middle class.

Take China: Just four decades ago, meat was a rare luxury. As incomes grew, so did their taste for pork. In 20 years, from 1995 to 2015, China pork imports shot from nothing to more than 800 metric tons annually. Iowa sent more than $115 million worth of pork to China alone in 2016, a 23 percent jump from the year before.

Japan, Canada, Mexico and South Korea also love pork and represent the leading customers for Iowa, which, in 2016, exported about $1 billion of pork.

It's hard to see all that as I drive past classic Iowa scenery—corn, and some soybeans, as far as the eye can see. Interspersed are the long hog barns. But I don't see pigs.

In fact, you can drive for hours through farm country in the state that raises a third of the nation's hogs and not see a single one. But they're there—and there's no denying their impact on the state economy.

- The pork industry contributed $756 million in Iowa state taxes in 2015.

- The industry provides about 550,000 jobs nationwide; 141,813 jobs in Iowa alone.

- Nearly 1 in 12 Iowan's have a job tied to pork; the industry provides more than $8 billion annually in labor income.

- More broadly, about 6 percent of Iowa jobs come from livestock.

When a new barn with about 2,400 hogs goes up in Iowa, it generates roughly 14 jobs and $2.3 million in sales, part of which goes toward the approximately $1.56 billion in federal taxes the pork industry pays each year.

The industry's "doing more with less, and years ago it became apparent to a lot of farmers, you had to grow or get out," says Ron Birkenholz, communications director with the Iowa Pork Producers Association.

But there is backlash on the ground. People I visit—union organizers, retirees, farmers, truck stop cashiers, former teachers and a bunch of people that live at the end of the road for a reason—say these massive farms have eroded the communal aspect of rural life and push small-scale farmers out of business.

"All I ever wanted to do was farm," Petersen says. "Then all this shit came up."

“It’s an entirely different system”

Nick Schutt outside his parent's home in Williams, Iowa. (Credit: Brian Bienkowski/EHN)

Fresh off work at the local grain elevator, Nick Schutt sports a cut-off plaid shirt and dusty jeans. He greets me with a strong handshake, his oil-stained paw engulfing mine.

He shows me his father's 80 acres, where Schutt still farms corn and beans and occasionally tinkers with a tractor or two. Long-haired dachshunds bark, a rabbit skitters under a trailer and a barn cat hides. His uncle lives directly across the road.

"He and my dad drive out and meet every morning on the lawn mowers to talk … 'You hear what happened to so and so,' " Schutt tells me.

Schutt, 43, lives a couple minutes away and stops by to check on his parents and have supper after work most days.

Schutt wheels his mini-van down the rutted dirt roads of Williams. We're about an hour north—and a world away—from Des Moines off I-35. "These roads are rougher than a cob," Schutt says, blaming the animal confinement operations—mostly hogs, some cattle—within a few miles of his house, which bring truck traffic that the roads weren't designed to handle.

Almost two dozen confinement barns, representing thousands of animals, all sprung up within the past decade or so.

Much like Petersen, Schutt only wants to farm. It's in his blood. The irony of living in rural Iowa these days, he says, is that—counter to the Farm Bureau's assertion about easy entry points—farming is increasingly a rich man's game.

"We live in a state where agriculture is the No. 1 industry, and I can't make a living farming," he says. "I've been farming my whole life."

In 1950 Iowa had about 206,000 farms total. The most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture Census found that farm total had dipped to 88,637.

But hog totals persist. Iowa has almost seven hogs for every human in the state. The next highest state, North Carolina, has less than half that amount at 9.3 million hogs. The money dwarfs other states too—hogs are a $7.5 billion a year business in Iowa—comprising one-third of the national total.

"It's still one of quickest and easiest ways for young people to get into farming: You can get a few acres, put up a barn, become a pork producer," says Iowa Pork Producers' Birkenholz.

About 94 percent of hog farms in Iowa are family owned, according to Iowa Pork Producers. NC Farm Families, too, boasts that families run more than 80 percent of North Carolina's hog farms.

But many are what are referred to as contract farmers—raising hogs for large corporations. The farmers own the buildings; the hogs they're raising are owned by Iowa Select Farms and Christensen Farms.

"It's not just that we're better at [livestock raising] now," says Patty Lovera, assistant director of Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based group focusing on corporate and government accountability relating to food, water, and corporate overreach.

"It's an entirely different system."

The companies dictate how the farmer raises and cares for the hogs: how much space the pigs get, what they're fed, how their health is monitored.

Contract farmers raise approximately 44 percent of all hogs and pigs sold in the U.S. But there's a flip side to the economic impact: While Iowa now sells twice as many hogs compared to three decades ago, their value has plummeted.

Lovera and colleagues found that between 1982 and 2007 in Iowa, the market share of the top four hog processors almost doubled, the number of hogs sold in Iowa doubled, but the economic value of hog sales, adjusted for inflation declined by 12 percent.

Corporate giants can absorb plummeting values, Lovera says. Smaller, individual farmers cannot. Over that time Iowa lost 82 percent of its hog farms, and counties with the highest hog sales and biggest farms had worse and declining economies than state averages.

"We see the closure of local barns, fewer small town vets, things like that as well," says Adam Mason, state policy director with the nonprofit Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. "The infrastructure that supported family farms started to disappear."

Agricultural economist, author and sustainable farming advocate John Ikerd remembers times past. As a young man in southwest Missouri, he noticed that if farmers in the small towns got wealthy, there was a "bit of jealousy." But the less fortunate gained too, as a prosperous neighbor meant better silo infrastructure, a wider selection of threshing equipment, stronger banks. The whole community was buoyed.

"Farms of the past were more than just farms," says Diane Rosenberg, president and executive director of Jefferson County Farmers & Neighbors, Inc., in Iowa. "There were more people working the farms, there was the infrastructure like grain elevators, lockers, and processers. These CAFOs [confined animal feeding operations] come, and the money leaves the communities."

Birkenholz, of the Iowa Pork Producers Association, counters that hog operations are buffering communities from larger trends tearing at their economic fabric. "We know that there are some counties, communities that aren't doing too well," he says. "But in many of them farming is still the only thing keeping them above water."

When I speak with professor and researcher Frank Mitloehner of University of California, Davis on the phone, his answer to consolidation is cold and pragmatic: "The farm of the past—you know, the red barn-type scenario, pigs out in the wild—those days are long gone," he says.

The traditional hog farmer "raised hogs, repaired planters, fixed tractors, ground and made their own feed, they bought fuel and seed and fertilizer," says Ron Plain, an agricultural economist from the University of Missouri. "They had an enormous number of decisions and things to worry about.

"The fact is that large operations can do what they do more efficiently and at lower cost than small operations. I can hire someone and train them to do two things or three things, and it's much easier than having someone do 200 or 300 things," he says.

Efficiency is one part of it; another is corporate control over all aspects of pork—from piglet to market. Before large industrial farms there was a predictable pattern: hog prices go up to profitable levels, producers over-expand production. Then prices go down, producers lose money, cut production, and prices go back up.

Such cycles, and the inherent inconsistent profits, discouraged corporations from being too involved. They like stability and growth to keep investors happy.

However, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, hog slaughter and processing corporations started buying large concentrated feeding farms, making them both suppliers and buyers of the hogs, Ikerd says.

In doing this, they gained control of the market, driving hog prices down to $10 per hundredweight (100 pounds) in 1998, the lowest price in 30 years. Independent hog farmers simply couldn't stay in business at these bottomed-out prices. Big hog producing states—North Carolina, Iowa, Missouri—lost about 90 percent of their independent hog producers when large industrial farms showed up, many turning to contracts or simply finding another way to make a living.

Petersen was one of these farmers, handed a foreclosure notice on the farm in the late 90s.

"We lost $70,000 in net worth, and our collateral—hog equipment, feeders—all at once were worth nothing," he says. It got so bad that the local bank came after his children's things—clothes and other items they bought themselves.

Back in Williams, Iowa, where Schutt lives, the county, Hamilton County, is the eighth highest hog producer by sales in the U.S. The county's average farm size is 406 acres and livestock provides an estimated 10 percent of the jobs.

Schutt points out roadside ditches he mows for free to get hay for his hobby horses. He shows me his boarded up basement windows, where the smell from nearby confinements barns would settle and permeate the house.

We shake hands goodbye around 8 p.m. For him, it's time for dinner with mom and dad, a short drive down the dirt road home, and a bit of rest before another day of two jobs, mowing ditches, and, if he's lucky, a bit of time to wrench on a tractor.

Just steps from the giant red barn on his dad's land he speaks candidly about what will happen when his father passes. "My brothers and I will get some land, I'll probably get 20 acres," he says.

"I guess it'd be nice to have one job."

Property value plummets

Graphic: Kaye LaFond

When Gail and Jeff Schwartzkopf bought their home just outside Rudd, Iowa, it was a country dream.

Within three months, a hog confinement was put up about 2,000 feet from their new home. Now hanging outside means gagging or being mobbed by flies. They can't sleep with their windows open.

"We simply can't go outside," Gail tells Petersen and I as we chat at her kitchen table. The smell—when manure is applied during the day and winds change at night—in nearby fields is so powerful they've woken at 2 a.m., running around the house to close windows.

"I used to be so active working in my flower beds, enjoying the wildlife and the summer breezes … all that stopped when the CAFO went in," she says, adding that being forced indoors has made her gain weight, which is "too depressing to think about."

Floyd County, ranks 77th out of 99 Iowa counties for quality of life, according to rankings by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a public health-focused philanthropy organization. Gail, who works at a nearby Love's Travel Stop, has had co-workers tell her that the smell is part of living in the country. "They have no idea," she says.

Birkenholz echoes Gail's friends. "Hogs have always stunk, always will."

"Yes there's odor, but it's not continuous and not on a daily basis," he adds.

Gail begs to differ, and Birkenholz admits that the relationship with large farms and neighbors isn't always perfect.

The Pork Producers Association is working with farmers to address these concerns, working with Iowa State University and other groups to site new barns where they'll have the least impact on neighbors. Another effort focuses on vegetative buffers, he says. A line of trees around a barn, he says, "can really knock down some of that odor."

Such buffers can also capture up to 74 percent of dust from large confinement operations, according to a 2016 University of Iowa study.

Gail and Jeff show me the trees they planted around their property when they moved in. Jeff talks about growing up on a farm, working with his grandfather. When I ask them if they've thought of moving, Gail turns the question back to me: "Where would we go?"

"At our ages there aren't a lot of choices for employment in another state," she adds.

And while Gail doesn't ask it, there's also a question—a big question—of who'd buy her home: Big hog farms tend to destroy nearby home values. A 2008 Iowa study of more than 5,000 homes found houses within three miles downwind from a confined animal farm lost as much as 44 percent of their value.

Homes not directly downwind still suffered a 16 percent loss in value. And size matters: every 10 percent increase in size for the nearby farm correlated with a 0.67 percent decrease in home value.Breaking point

The view from Gail and Jeff Schwartzkopf's front yard. (Credit: Brian Bienkowski/EHN)

There's an undercurrent of rural rebellion in Iowa, and a lot of people are arming themselves with new knowledge about water, air, zoning and pork politics.

"I never thought I'd be an activist," Gail Schwarzkopf says, a refrain echoed from almost everyone I visit in Iowa.

Petersen and I leave the Schwartzkopf's and hop back on the highway. We climb in his Subaru and he ignores the car's seatbelt alarm.

His eyes are bothering him badly — "Damn diabetes," he says. He opens up to me about a troubled upbringing in Iowa, including a veteran father who returned to the U.S. only wanting to farm but who ultimately received a foreclosure notice—just as Petersen did in the late 90s.

Petersen's sore eyes tear up, but only briefly. He has a sick hog to deal with, an upcoming trip to DC, and more communities to rally.

Hell isn't going to raise itself.

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms.