This is part 3 of a 4-part investigation of the science surrounding the chemical BPA and the U.S. regulatory push to discredit independent evidence of harm while favoring pro-industry science despite significant shortcomings.

MOSCOW, Idaho—Patricia Hunt, a geneticist at Washington State University, and I walk a long, curved route through the arboretum at the University of Idaho — past the big red barn, through the woods and up a hill by the water tower painted with a big yellow "I". It's the same water tower we could see directly out from her back patio. Yet our path back to the house was a far more natural course than any straight-line path.

Such a lack of linearity, Hunt explained, can also describe the relationship between the dose of a chemical — say, bisphenol A (or BPA) — and its level of impact on the body.

Historically, government toxicologists have assumed that the greater the exposure to a toxic chemical, the greater the harm — or, as the old adage goes, "the dose makes the poison." A dose-response curve should therefore always be monotonic, meaning it will never change direction from positive to negative, or vice versa. But academic scientists, especially those who study endocrinology, are finding that this principle is not always true, at least not for chemicals such as BPA that mimic and mess with our hormones. These endocrine-disrupting chemicals, studies show, can wreak havoc at extremely small doses.

This disagreement is just one of many front lines in an ongoing conflict between federal regulators and academics, which intensified with the launch in 2012 of a multimillion-dollar government-led project called Consortium Linking Academic and Regulatory Insights on BPA Toxicity, or Clarity for short. The project combines a traditional regulatory toxicology study from the government — dubbed the Core Study — and investigational studies from academics. The government and most of the 14 participating academic scientists have completed their respective studies for the collaborative project. An integrated report that pulls together all the findings is currently underway and expected to be completed by the end of 2019.

The goal of Clarity is to reconcile a long-standing dispute over data and conclusions on BPA's health effects, although the implications could be far broader. BPA is just one of hundreds of chemicals we're exposed to in our everyday lives that are suspected of scrambling the natural hormone messages in our bodies.

Related: Check out "Clouded in Clarity," a comic strip adaptation of this series

Through interviews and emails obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests, EHN found a series of red flags concerning deficiencies in the FDA's science on BPA, including how it dictated much of the Clarity study design and methods. As EHN detailed, a number of these factors limited Clarity's robustness to detect health effects — from insistence by the FDA to use of a strain of animal that had been shown to be insensitive to hormone disruptors, to the choice of a stressful means to deliver BPA to the animals, to the provision of small numbers of animals to some of the academic scientists.

But then there's the question of what happened as the data came in. What patterns did researchers look for when plotting the dose of the chemical versus the response of the animals? Where did they draw the line on what is considered significant evidence of an effect? And how did they present what they found? Once again, a number of contentious issues emerged in the course of EHN's investigation.

Take North Carolina State University biology professor Heather Patisaul's research on the brain: In three studies now, including one that was published as part of Clarity, she has found effects of BPA on the developing rodent brain at just 2.5 micrograms per kilogram of body weight. For context, that is approximately 120,000 times below the lowest dose that has been shown in other studies to alter uterine weight — one of the traditional tests looked at by the FDA.

In some cases of what scientists call non-monotonicity, a chemical may have effects at low doses and no effects at higher doses; in others, further effects may only appear as doses get really high. In either case, the result is a curve that changes direction, such as a U-shape. But if researchers were to only look for a strictly increasing line, by enlisting the statistical methods best suited to identify a linear trend, then their calculations would likely conclude that the chemical has no impact on that endpoint of interest.

It's also possible that the health effects of a chemical differ across doses. "Very high and very low doses can do entirely different things," Frederick vom Saal, a professor of biology at the University of Missouri-Columbia and a Clarity investigator, told EHN. Take, for example, diethylstilbestrol (DES), the estrogenic drug that was once commonly prescribed to pregnant women. Studies have found that exposures in the womb to 100 parts per billion of DES can cause mice to become scrawny as adults, while exposures to 1 ppb can result in severe obesity. There is only one way to fairly evaluate a dose-response relationship, Richard Stahlhut, a biologist at the University of Missouri-Columbia, told EHN. "You look for straight lines, you look for curves," he said. "Then you tell people what you found."

However, A. John Bailer, chair of the department of statistics at Miami University in Ohio, is among scientists not fully convinced of non-monotonic dose responses. He underscored a need to better understand their biologic basis. "A mechanistic understanding would give us the real insights," he told EHN.

Scott Belcher, a biologist at North Carolina State University, and a Clarity investigator, pointed to a number of studies that provide evidence for cellular mechanisms driving these non-monotonic responses, including opposing effects from multiple hormone receptors and negative feedback loops, a key regulatory mechanism in living things.

"Most simply put, biological systems are complicated and are controlled by multiple types of regulation," he told EHN.

Despite the large body of evidence from vom Saal and others, the FDA continues to deny the relevance of very low dose exposures and non-monotonicity. In an email to EHN, Marianna Naum, an FDA spokesperson, said that the agency had "extensively reviewed the low-dose BPA literature and was "unable to construct a plausible or logical comprehensive toxicological profile or explanation for the many claimed effects of BPA, largely due to the inconsistencies that currently exist within this literature."

This attitude keeps the stalemate alive, while we all remain Guinea pigs in a grand experiment on our hormones. "We thought Clarity would help, but the way the results turned out, it has kind of exacerbated the difference between people who think of low-dose effects as important and non-monotonic dose-responses as real and physiologically important, and those that don't," said Jerry Heindel, the health scientist administrator at NIEHS when Clarity was initiated. "That's the biggest hurdle we still have to get through."

On the hunt

Hunt abruptly stops during our stroll through the arboretum, which is just across the state border and a few miles from her lab at Washington State University. "Look, a wild orchid," she said. Pink petals pop in the otherwise predominantly green landscape.

Unexpected discoveries may be a relatively frequent occurrence for Hunt: She has twice found bisphenols coursing through the bodies of animals not intentionally dosed with a chemical in her studies, a result of degrading plastic cages housing the mice. Generally, however, scientific research tends to be a bit more prescribed. To find any particular effect of a chemical, you usually need to look for it — or at least recognize it. The problem is, government regulators and academics tend to look for and recognize different things: Regulators look for the obvious – changes in body weight, or a fast-growing tumor. Endocrinologists look for subtle changes – learning behavior, anxiety, memory – that may not appear until years later, or even subsequent generations. This has been another major point of contention in the ongoing debate over the testing and regulation of endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

"Typically, the tests they use for regulatory purposes are a little more rigid. They are not as cutting edge as you might see from academic labs doing it on their own," said John Meeker, an environmental health scientist at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, who is not involved in Clarity. "This can lead to big differences in study conclusions, as well as the overall view of the toxicity of a particular agent."

Related: A scientific stalemate leaves our hormones and health at risk

In one of University of Illinois at Chicago researcher Gail Prins' studies, for example, she found that while BPA didn't appear to stimulate prostate cancer by itself, if there was an early life exposure to BPA, an additional estrogen or testosterone exposure later in life then significantly increased the risk of prostate cancer. The most significant effects appeared in the lowest dose groups.

Other Clarity studies by academic investigators found a number of low-dose BPA effects, including changes in gene expression within specific regions of the brain, ovarian follicle development and spatial navigation. "The government keeps testing chemicals for safety using the same old approaches developed 50 years ago, and then they tell us that everybody is good to go," said Laura Vandenberg, an environmental health researcher at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst's School of Public Health and who was not involved in Clarity. "You don't have to see a tumor to determine something adverse is going on."

In an email to National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) colleagues in February 2018, Nigel Walker, a toxicologist at NIEHS who helped lead the study, highlighted one of the key questions that Clarity aimed to answer: "Are we missing any signals using 'traditional' approaches that newer technologies and approaches pick up"?

High bars

University of Missouri researchers Fred vom Saal and Wade Welshons. (Credit: Brian Bienkowski)

Which is worse, deeming something as safe when it's not or saying something causes harm when it doesn't?

The two scenarios are referred to, respectively, as false negatives and false positives. "The FDA uses very, very conservative statistics with a low risk of false positives," said Patisaul. "That's always been a sticky wicket with the FDA versus academic scientists."

By applying conservative statistics throughout the Clarity Core Study that generally minimize false positives, noted Patisaul, the government increased the risk of false negatives — or the chance of deeming a chemical innocent when it was actually guilty of harm.

It is a balancing act, explained Bailer. With conservative methods, you may be less likely to see real effects. "But the counter response is: You are less likely to see false effects," he told EHN.

Even with a high bar, statistically significant effects emerged from the government's data. In tests for mammary gland cancerous growths, for example, the Core Study detected significant effects at the lowest dose of BPA in the part of the study where exposure stopped when the rats were weaned. But through the government's "weight-of-evidence approach," they discounted the finding as "unlikely" to be a "plausible BPA treatment-related lesion."

Their rationale: similar effects were not observed at the highest doses, the effect was not observed in animals exposed over their entire lifetimes and, as noted earlier, lesions were found in historical controls. (EHN gave the FDA a chance to comment, but the agency declined.)

Researchers Ana Soto, Carlos Sonnenschein and Silva Krause looking at mammary glands from a BPA experiment at Tufts University. (Credit: Ana Soto)

Patisaul disagreed with their methods and rationale. "There are certainly cases where developmental-only exposure has different effects than lifelong exposure," she said. "Just because you don't know why something is happening doesn't mean that the phenomenon is erroneous or 'not biologically plausible.'"

"This attitude is certainly not precautionary nor protective of public health and emphasizes the lengths to which this group will go to bury potentially important outcomes," added Patisaul.

Vom Saal said he faced a particularly high bar to uncover potentially important outcomes in his Clarity study. The weights of the rats that the FDA provided him for analysis of the effects of BPA on the development of the urogenital system, he explained, ranged widely — the heaviest rat weighed at least 250 percent more than the lightest rat. To prevent bias, all Clarity scientists were blinded to the BPA exposure levels of the animals and tissues that they received for study. Once the data were unblinded, vom Saal learned that his BPA-unexposed rats also weighed significantly less than the BPA-unexposed rats in the government's Core Study.

Increased variability in weights could cause increased variability in other measures of interest. A statistical fallout of that variability can be a watering down of the differences between exposed and unexposed rats. "This was just not done correctly," said vom Saal.

Deciphering data

On the winding walk through a densely wooded portion of the arboretum, Hunt points out an abundance of money plants — their bright magenta blooms scattered across the forest floor. "They are weeds," she says. "Or wildflowers, depending on your point of view."

Again, two different people can be looking at the same thing yet call it two very different things — whether out in the world or in the lab. And it can be a result of bias, noted Bailer. "The eye wants to see what the eye wants to see," he said, suggesting that a scientist might, for example, see a non-monotonic pattern in data where such a dose-response effect does not actually exist.

Further, two different scientists may also take the same findings and make a number of different choices that ultimately weave a very different story for the public. What results do they include and how do they interpret those results? Which of the results do they emphasize in the study's conclusions, abstract and title? How do they publicize that end product to the rest of us?

Prins argued that the FDA has repeatedly come up with study results that show effects of BPA, "but then spin it in the discussion section to say there are no BPA effects."

Critics suggest that the FDA may spin results across studies as well. For example, FDA risk assessments have generally relied largely on a small number of older industry-funded guideline studies. "The playing field is slanted. Industry gets more input," said Hunt.

The FDA's 2014 risk assessment of BPA is one such example. Of the 36 studies that they identified as related to neurological endpoints, the FDA chose only one to include in the risk assessment. That study was funded by industry. Then, of 25 reproduction-related studies, they determined that none were appropriate for the risk assessment as they did not follow the validated protocols traditionally accepted by the FDA.

"If you cherry pick for the answer you want, you can get it," said Patisaul. "I would argue that's not in the interest of public health." When the FDA declared BPA "safe" in its previous 2008 risk assessment, reporters at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel dug up evidence that the decision was influenced by the American Chemistry Council, a leading industry trade group.

Further, the FDA's science review board rejected the conclusions in that assessment.

By 2008, more than 1,000 studies of BPA health effects had been published yet the FDA based its conclusion of BPA's safety on only two studies, which were funded by the plastic industry and had been deemed flawed by outside scientists and government officials.

The agency defends their risk assessments of BPA. "Guideline and academic studies are independently evaluated on a case by case basis to determine if enough information is available to have confidence in the data to address the relevant risk assessment question," Naum, the FDA spokesperson, wrote in an email to EHN. "The FDA's conclusions were based on a comprehensive, transparent, review using predefined scientifically supported criteria for evaluating the available science."

Clarity provides yet another opportunity to combine a lot of data into a more comprehensive assessment of BPA. An analysis of all the data from the collaboration remains in the works. "This is where we are going to get the most compelling evidence," added Hunt.

Still, just what the feds will do with that evidence remains unclear. The FDA did not respond to questions concerning how it will use the Clarity findings, or what it would take for the results or conclusions to prompt the agency to revise its view on the safety of BPA or the criteria for determining a safe dose of a chemical. Naum only stated that the agency will "continue to monitor developments in the field," including previous reviews and the results of the Clarity Core Study, and will "take steps appropriate to protect public health."

In an email on May 8, 2012, Retha Newbold, a developmental endocrinologist with NIEHS, wrote to Walker, the toxicologist at NIEHS, of her disappointment in not getting more assurance from Jason Aungst, the toxicology branch chief at the FDA, that the agency would use the data generated from Clarity. "He is already planning his reasons why they may not use it," she wrote. Aungst helped lead that 2014 risk assessment.

Walker responded: "Like most data for FDA one can only ensure data 'can be used' for decision making, not that it 'will be.'" In February 2018, he emailed other NIEHS colleagues lamenting a lack of a "plan, timeframe or strategy" from the FDA on how it "plans to do an update to its assessment of data on BPA."

The final word

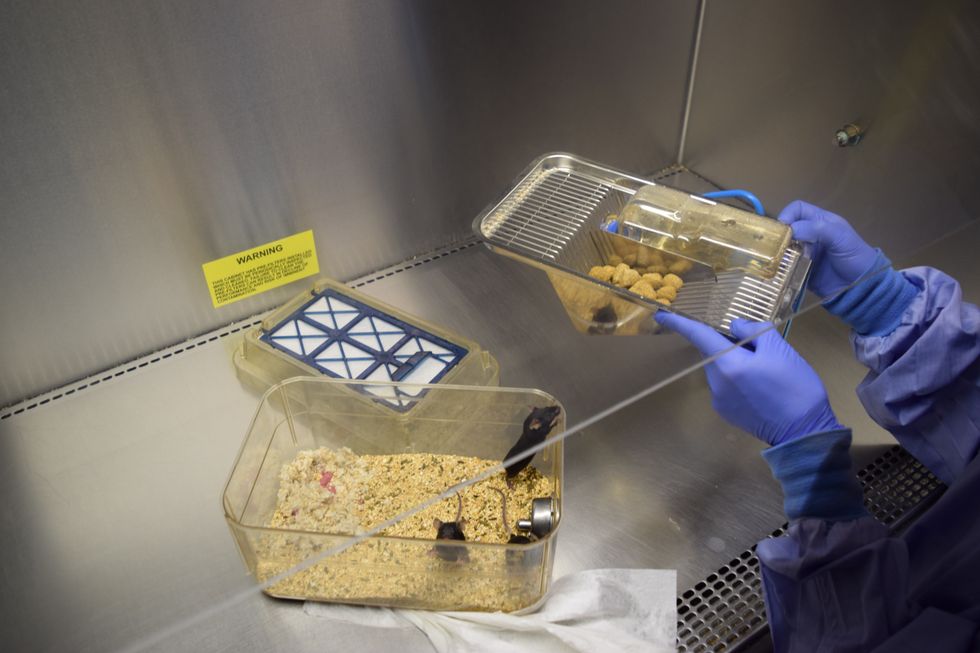

Mice from Pat Hunt's lab. (Credit: Lynne Peeples)

Degraded cages from Pat Hunt's lab. (Credit: Lynne Peeples)

Leaving a room filled with plastic cages of mice — big brown ones and tiny pink ones — Hunt and I step onto a sticky mat and change out of the Crocs we had worn inside. The process helps to ensure further contaminants including pathogens are not spread to the mice in the lab. We place the Crocs back on shoe racks just as one of Hunt's colleagues walks by holding an empty reusable pod for a Keurig coffee machine. She looks knowingly at Hunt and says, "unfortunately, it's plastic."

Hunt reassures her that, actually, this one is made of silicone. "So, you're ok," she says. "But good on you to think about that."

Not everyone thinks about the potential health risks of BPA, let alone the hundreds of other endocrine-disrupting chemicals found in common consumer products. Not surprisingly, scientists who study the chemicals for a living are more apt to consider exposures. Hunt, for example, now opts for email receipts on her stops by the Moscow Food Co-op. She knows that most cash register receipts, too, are among the everyday things that can leach BPA or one of its substitutes, such as bisphenol S, onto the skin and into the body.

Some scientists fear that the public has not been receiving accurate information on BPA. A curious consumer might look for answers online. Yet the top hit in a Google search of "bisphenol A safety" is a link to an industry-sponsored website titled "Facts About BPA." In fact, the search result appears in a stand-out box filled with material pulled from the site. Without having to click a link, you could read that BPA has a "safety track record of 50 years," and that no "cause-and-effect relationship between BPA and any human health effects" has been shown.

Patisaul suggested that the public has also not been receiving the "correct message," because "the FDA has been issuing statements before research has been done and before they've had a chance to comprehensively look at all the data."

The most recent case-in-point was a late February 2018 statement from Stephen Ostroff, the deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the FDA, which highlighted the agency's interpretations of the just-released draft of the Clarity Core Study. It did not mention the significant findings of effects at low doses of BPA in both the Core Study and in the peer-reviewed studies from academic collaborators that had been published by that time. National headlines appeared shortly thereafter. From NPR to Newsweek, the media was once again relaying the message from the FDA that the public need not worry about BPA.

Clarity participants had agreed at the start of the project that they would not make any policy statements, nor any conclusions, without considering all of the data. Even NIEHS was caught off-guard by the FDA's move. Earlier in February, Virginia Guidry, of the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison, emailed Walker and other colleagues about a conversation she had with a communications official at the FDA regarding the Core Study release. "I told her we were planning a reactive approach, ready for questions but no press release. They are doing the same," she wrote.

"The announcement from the FDA that has spread like wildfire is in direct contrast with that agreement," said Patisaul. "We had published four papers. Other Clarity participants had published papers. And the FDA said nothing. Then, when they issued their draft report — which was not even peer-reviewed — they made this big sweeping statement that BPA is fine. That's disingenuous."

Pete Myers, CEO and chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, suggested that the move was a tactic by the FDA to control the media. The press — and the public — would pay less attention when the full report is unveiled, he told EHN. "The second wave doesn't receive the same coverage," said Myers. (Editor's note: Myers is also the founder of EHN, though the publication is editorially independent.)

A fury of emails between NIEHS colleagues followed the FDA statement. In one of those emails, Walker suggested that FDA officials had drafted "a statement to reiterate their current policy stance on the safety of BPA." The FDA did not respond to EHN's questions regarding why they issued the statement. They further declined to respond to the subsequent criticisms.

On that industry website, which belongs to the American Chemistry Council, three key findings from the government's research on BPA are listed. One of them has been front-and-center in Clarity: "No risk of health effects at typical consumer exposure levels." Hunt and other non-government scientists have co-authored a paper currently under peer review that also calls into question the other two: "Consumer exposure to BPA is extremely low" and "BPA is rapidly eliminated from the body."

"We are woefully underestimating exposure levels," said Hunt. "All of our regulatory decisions have been based on assumptions about metabolism and levels of human exposure that are questionable."

The stakes are high. With BPA just the tip of the iceberg, any conclusions and admission by the FDA of BPA's problems could cause the dominoes to really fall. It would be "like a death knell for industry," she added. "I think the feds are very sensitive to that."

In part 4, EHN takes a look toward the future of BPA, its alternatives and what experts suggest still needs to be done regardless of the outcome of the integrated Clarity report.